When Students Create Their Own AI Policies

Eight high schoolers made their own rules for AI use. What they came up with might shock you.

“Do you use AI in school?”

As soon as the question left my lips, I realized its weight.

In a classroom bustling with conversation, I managed to unintentionally silence my corner of the room. “You’re asking us some hard-hitting questions, Mr. Davis”, said Alexis, her observation slicing through the awkward silence. She proceeded to retreat into her combo desk, her four fingers serving as a flimsy barrier for her bashful smile, her two groupmates responding similarly.

What was meant to be a softball question during an introductory speed-friending activity revealed just how touchy a subject AI was for my students, all of whom are rising high school seniors in my college-level Education Technology course that commenced last week. This brief interaction made me more eager to see how they would approach our AI Policy Draft assignment.

In the fourth class, I posed the following scenario to my students:

You’re one of two teaching assistants (TAs) for a course offered at Georgetown University. The course is taken by mostly first- and second-year students. As the professor prepares for their upcoming fall class, they ask you and your fellow TA to come up with an AI policy for the course.

The assignment—which challenged students to apply learning science and their understanding of how generative AI platforms work to create an AI policy for a college course—revealed that when students are given adequate tools and time, they can generate policies that are more conducive to their learning than educators. Not only does this article give insight into what 17-year-olds think about when and how to use these platforms, but it uncovers an eye-opening truth: today’s K-12 students aren’t learning to think critically about the role of AI in their lives, and university professors are left holding the bag.

I split the students into four pairs of two. Each pair was instructed to choose their course title and create an AI policy that included the following:

Acceptable and unacceptable use cases that promote learning and minimize the likelihood of academic misconduct

At least one recommended tool for each acceptable use case

When and how students should cite AI

I also linked a few resources for them in Canvas to jumpstart their ideation process:

ChatGPT and Generative AI Tools: Sample Syllabus Policy Statements (University of Texas at Austin)

Consolidated AI Policy Document (Pages 18 and 19, Council of Independent Colleges)

Generative AI platforms: Perplexity, ChatGPT, Claude, Copilot

Students had 40 minutes to draft their policies, followed by 20 minutes of discussion. Here’s an example of what one pair came up with:

Student-Generated AI Policy Example

Course: English Literature

Regarding AI

Within the English Literature course, work submitted by a student must be created and written by the student. Whether it is group work, an individual assignment, or a final project, all works must be your own. While usage of Artificial Intelligence is allowed, it is allowed in heavy moderation. AI is not allowed to write a student’s work for them. Usage of AI is monitored within this literature course and all students admitted within the course are expected to act on academic integrity upon enrollment.

Acceptable use of AI

Search for word or phrase definitions

Generate questions and writing prompts to aid in writing analysis portions (ex. generating rhetorical questions to help start analysis in a writing prompt, NOT generating the analysis portion itself)

Spell check work and correct punctuation

How to properly credit AI

Mention the AI software in the works cited section

Use MLA format on citations

Add the sources pulled by the AI from the search

Recommended tools

Grammarly (Grammar and Punctuation)

QuillBot (Grammar and Punctuation)

ChatGPT (Grammar and Punctuation, Generate aiding questions, Terms and Phrases)

Copilot (Grammar and Punctuation, Generate aiding questions, Terms and Phrases)

Perplexity (Grammar and Punctuation, Generate aiding questions, Terms and Phrases)

Consequences for improper use

Improper usage of AI is a violation of academic integrity and a form of plagiarism. Consequences for improper usage of AI within this course include but are not limited to:

Attending a meeting with the instructor

Receiving a failing grade on the assignment submitted, incomplete or not

Meeting and discussing with your academic advisor and dean

Depending on the severity, punishment may result in suspension, or expulsion

What Faculty Can Learn From Student-Created AI Policies

I read equally detailed policies from TAs in social studies, statistics, and psychology courses, and each policy had its strengths and weaknesses. The English Literature policy above has a crystal clear acceptable use case section. Word and definition searches, generating rhetorical questions to aid idea development, and fixing spelling and punctuation are specific use case descriptions, more helpful than general recommendations to use AI for “brainstorming” or “grammar.” They listed the consequences for AI misuse, but a list of possible reprimands without a clear explanation of which actions would trigger each consequence may cause students more anxiety, not less.

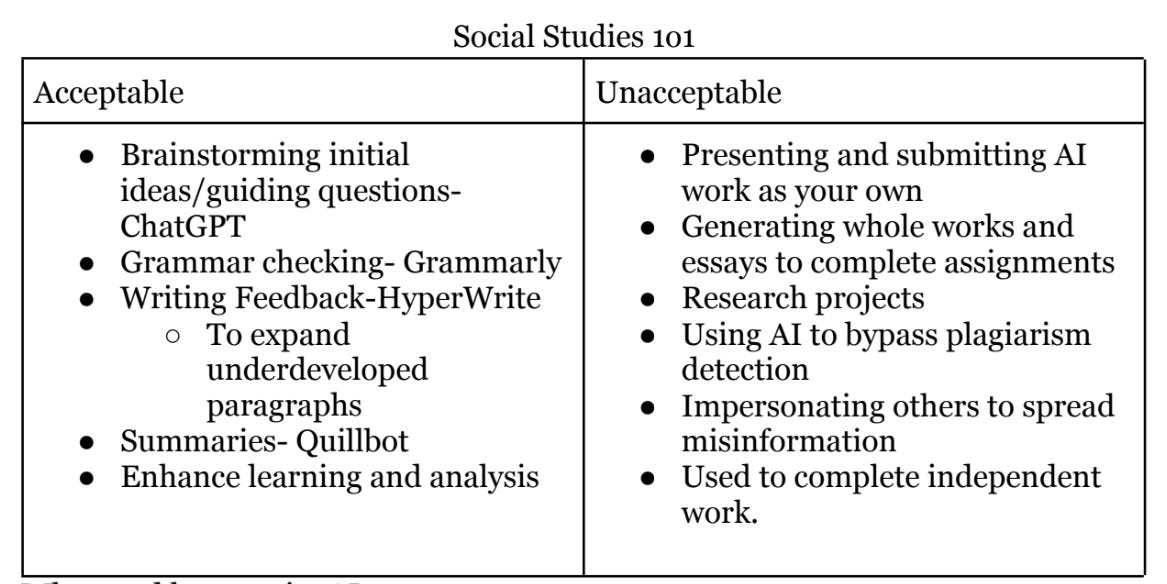

The image above is a table from the social studies policy outlining acceptable and unacceptable use cases. While there’s some specific guidance, such as refraining from using AI humanizer platforms, the policy contains some contradictions. If students use HyperWrite—a close cousin to Grammarly in the world of AI-powered writing assistants—to expand underdeveloped paragraphs, that sounds like using AI to complete independent work, which this policy prohibits.

I was blown away by my statistics TAs, who gave a robust description of when and how to cite AI. Here’s what they wrote:

When: Students should cite AI if they used it to compare answers or as a method of remembering a certain formula. Using it for grammar checking isn’t totally necessary, but if a student feels compelled to share what they used to check grammar, then that’s fine too.

How: Cite the AI using any format (preferably MLA) and how you used it on large projects, mention it in the comments on Google Classroom or any other online class website for regular assignments.

MLA example:

In text citation: ("Describe the symbolism")

Bibliography: “Describe the symbolism of the green light in the book The Great Gatsby by F. Scott Fitzgerald” prompt. ChatGPT, 13 Feb. version, OpenAI, 8 Mar. 2023, https://chat.openai.com/share/dccb3610-1db9-4eed-88b1-cdb06f67982a.

APA example:

In text citation: (OpenAI, 2023)

Bibliography: OpenAI. (2023). ChatGPT (Mar 14 version) [Large language model]. https://chat.openai.com/share/dccb3610-1db9-4eed-88b1-cdb06f67982a.

Acceptable Prompts

Is a2+b2=c2 the correct formula for Pythagorean theorem?

I got 7 for x+8=15, is that correct? If not, explain why.

I couldn’t help but focus on the acceptable prompts piece. Though impressed with the clarity and foresight, I was left wondering the following: What would incentivize a student to generate a human answer before an automated answer when the automated answer is just a click away?

After about 40 minutes of pair work, students discussed their policy and rationale with a neighboring group for about 10 minutes. Then, we all came together and spent the last 10 minutes of class discussing the activity.

I asked students how their self-created policies compare to the guidance they receive on AI in their schools. Two distinct approaches emerged: school-wide AI bans or heavy teacher supervision. My students—all entering their senior year of high school—shared accounts of their peers being publicly humiliated by teachers for misusing AI on tests and big assignments. One student from New York admitted they’d never used an AI platform before my course, and that their school had a low-tech culture that didn’t promote digital literacy. Two students who attended the same Texas school said their AI use was highly regulated; they could only use it on specific in-class activities when the teacher explicitly gave them permission. They were often required to use browsers that prevented them from opening multiple tabs.

This discussion contextualized the anecdote at the top of this article. All eight of these high-achieving students were fed a popular narrative about AI: the “bad” students use it, the “good” students don’t. Even when they could use AI in class (never at home), their use was narrow and highly surveilled. There was no experimentation or discussion about implications for their learning, professional careers, or the world at large. Perhaps this is unsurprising, but this was the first time I’d ever experienced students’ anxiety and frustration about their experience with AI in K-12. It was palpable through the stories they told, a palpability that news articles can’t convey.

As they began to pack up their belongings, I snuck in one last question: “Would you follow your own AI policy?” Eyes turned to the ceiling, except for one student, Alijah, who responded without hesitation: “I feel like I already do.”

Looking back, this response shouldn’t have surprised me, either. These were “good” students, the best and brightest from their schools, nominated for this special summer college immersion program—of course, they were rule followers. What I should have asked is whether they want to follow these rules or not.

I wonder whether they feel like these rules (in their schools, the ones recommended by flagship universities, the general narratives they’ve been fed about AI) are helpful for their personal development and aid the construction of a good society. If I took away the templates and assignment criteria, what policies would they have generated?

You could take the best bits from each student policy and Frankenstein a pretty robust policy applicable to any college-level course. It would be a long policy, but the thoughtfulness is necessary to respond to AI’s disruptions in education.

My takeaway: Students enter our courses with vastly different perceptions of and experiences using AI. Adding layers to our existing AI policies—explicitly listing acceptable and unacceptable use cases, defining nebulous terms like “brainstorming” and how students should use AI to do it, offering recommended tools and citation formats—is a start, but it won’t be enough. We must talk to our students about AI. Walk through your policy, describe how and why it’s constructed, and reflect on how it will help their personal and professional development. The 30 minutes we spend on this, either in class or in a discussion post, will divert their mental capacity away from logistics and consequences and toward our ultimate goal: learning.

If you enjoyed this piece, you might also enjoy: