How to Stop Your Students from Cheating with AI

Generative AI didn't create cheating - it just made students more efficient at it. Here's how to put an end to it.

In my high school and college years, people often asked me, “How do you stay motivated to go to the gym?” As a naive and arrogant teen, I would talk about my undying commitment to my morning routine and how exercise was a lifestyle, not a vain pursuit of a slimmer body.

The truth is that part of my motivation—in addition to my fatphobia and early initiation into gym culture through my participation in organized sports—came from the fact that someone taught me how to bench press when I was fourteen. I learned among an intimate group of male and female students in an elective weightlifting class in my freshman year of high school. Although our group consisted of various body types, physical abilities, and confidence levels, we all possessed a similar ignorance about lifting.

I speak for myself in saying that the experience was far from humiliating; our teacher was patient and cared for both our safety and progress toward our self-determined strength goals. Learning how to lift weights was a critical point in my adolescent development: I gained autonomy over my body from learning how to safely and effectively exercise. Eliminating the risks of embarrassment and serious injury from incorrect form removed two major barriers between me and the weight room.

Dangerous Lifting

If learning is to student success what weightlifting is to an muscular physique, then most students are lifting without training—they were never taught how to bench press. We expect students to be resilient: to take chances in their learning, to fail, admit and reflect on those failures, and confront those same problems with a different approach. We expect them to study efficiently, research responsibly, speak articulately, and write precisely about what they know and desire to know. We expect them to learn while they’re grieving, exhausted, lonely, anxious, and despondent about the state of the world.

We’re expecting students to be self motivated to do things they’ve never been taught to do. Most high school and college students have never been taught how to learn, but we expect students to learn without cheating. The facelessness of generative AI platforms makes it harder for students to agree with the moral arguments against academic misconduct. Not only have we punted on the idea that metacognition should be a general education requirement at the high school and college levels, but we also continue to see faculty teach courses that fail to promote learning at all.

In the tsunami-sized wave of AI webinars proliferated across digitized academia, most focus on two primary dimensions of AI use:

1) Industry-specific AI use - for example, a business school might host a webinar about AI’s use in Excel for accounting, or a law school would host a webinar about AI for legal research. These are specialized, discipline-specific AI skills that institutions are teaching through co-curricular engagements.

2) AI in teaching - for example, a college teaching and learning center might host an AI workshop about how faculty can use AI to grade or give students feedback.

A third dimension that hasn’t been discussed nearly as much is AI in student learning. I’m not talking about using generative AI to outline a paper; that’s AI in assignment completion. I’m talking about evidence-based metacognitive strategies that lead to critical thinking. Popular strategies include previewing, inquiry-based reading, mind mapping, concept mapping, reflective journaling, interleaving, brain breaks, chunking (for studying), retrieval practice, idea generation, and peer teaching.

If you’ve never heard of these strategies, you’re not alone. This is because we don’t teach students how to learn; we teach them how to regurgitate information (worst), apply the skills needed to complete our assignments (better), or both.

A Simple Litmus Test to Determine Whether Your Class Promotes Cheating Behavior

Think of a student in your class that you’d like to see grow in a certain area. This could be a student who chronically turns in their assignments late, or who suspect may be using AI irresponsibly. Could that student answer the following questions?:

If it’s 11:05pm and my paper is due at midnight, but I’m only halfway done the paper, how can I submit it as close to the deadline as possible while displaying my progress toward the learning objectives in the assignment, even if what I submit is incomplete? Can I resubmit the assignment at a later time?

When I’m given a big project in week 5 of the semester and I have 11 weeks to complete it, how do I set progress benchmarks so that I’m not waiting until the last minute? How can my peers hold me accountable to those benchmarks?

What processes do I have to reflect on the information shared in this week’s lecture?

What were the learning goals for this week? How do I assess whether I’ve reached those goals?

When I have a learning block—writer’s block, a bottle neck in my research, difficulty expressing my thoughts—what is my go-to response? Can I identify the specific thing that’s got me stuck?

Is there a final exam for this class? If so, how is this assignment preparing me to perform well on that exam?

How many chances do I have to “get this right”? Will I fail the class if I don’t?

Do my classmates and instructor create an environment that encourages me to consider these aspects of my learning?

If that student can’t answer more than four of questions above—or answers “no” to question 8 and the second part of question 1, and yes to question 7—they will probably cheat in your class, whether you ban AI or not.

These questions address common reasons for cheating: rigid or unclear expectations for how progress toward learning goals is evidenced, analysis paralysis (which can lead to procrastination, which then can lead to cheating), lack of academic resilience strategies, “busy work” or what students perceive to be irrelevant assignments, and high-stakes assessments that make students feel like ‘getting it wrong’ yields catastrophic consequences.

Generative AI didn't create cheating—these reasons have existed for decades. AI has made it easier for students to cheat, and in some cases, more challenging for educators to catch them. Demonizing the students or the technology they use to respond to the above circumstances is wasted energy. Instead, we can focus on solving the problems above. The more reasons we make obsolete, the less reasons students have to cheat.

Where We Go From Here - Curricular and Classroom-Level Solutions

If we don’t give students metacognitive skills and critique the traditional pedagogies that are conducive to cheating, we’ll be having the same AI cheating conversation forever, until we reached the point where the AI professor is more common and useful than the human professor. The future of AI in learning depends on the conversations we have now.

The Ideal Solution

The ideal solution would be for universities to make metacognition a general education requirement, eliminate the credit hour, make college cheaper, and eliminate, bolster wellness services, and eliminate institutional pressures that lead to academic misconduct.

In the meantime, faculty have a unique opportunity to teach students how to learn. University academic services centers might already be leading trainings on metacognition. As valuable as they are, those are voluntary and likely attended by the students who need the strategies the least. If we focus on it in courses, we make sure that all of our students learn these skills.

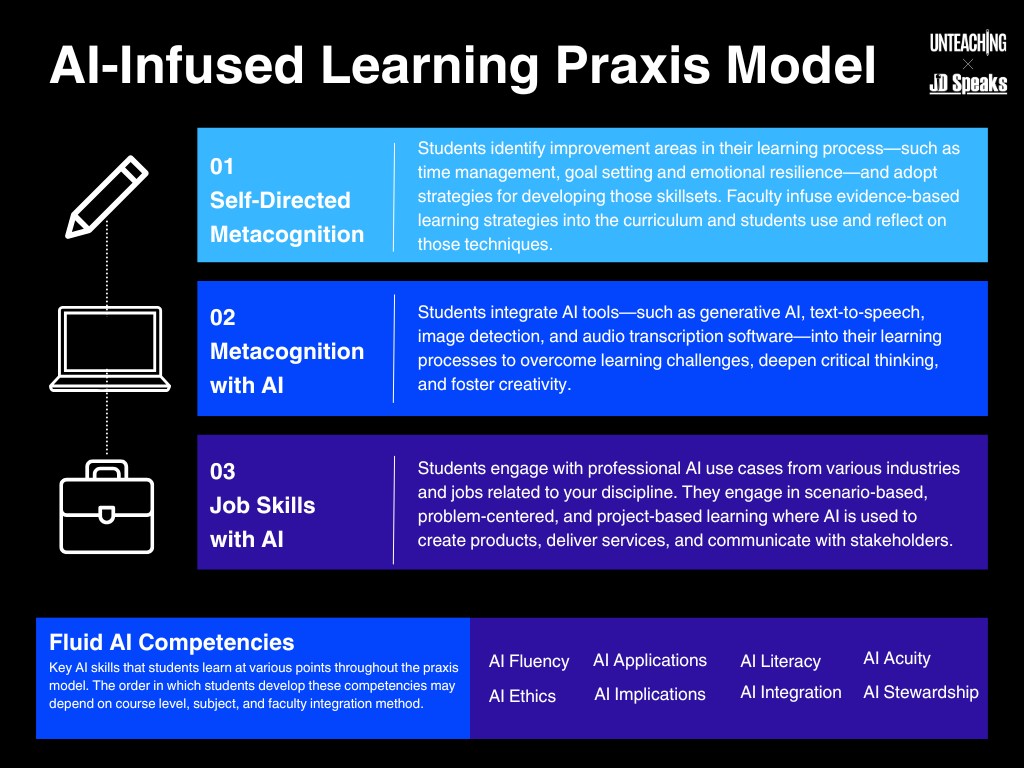

Once students learn how to dissolve the reasons for cheating without AI, faculty can introduce AI as a tool for their learning to make the extinction of the cheating reasons more permanent. Then, once students have had practice using AI to study, write, and critically think, we can teach them the job-specific AI use cases we’re currently discussing. I created a praxis model for this:

How to Embed Metacognition Into Your Teaching

I’m aware that your course content is plentiful and class time is limited. Replacing just 5% or less of your planned content with activities and reflection on metacognition will likely make the remaining 95% more valuable to your students. When responding to the “but there’s no time” rebut, I often go to Grant Wiggins’ quote from an article he wrote on giving effective feedback:

“Although the universal teacher lament that there's no time for such feedback is understandable, remember that "no time to give and use feedback" actually means "no time to cause learning." As we have seen, research shows that less teaching plus more feedback is the key to achieving greater learning.” - Grant Wiggins

Replace “feedback” with “metacognition”, and the above quote’s accuracy still stands.

The easiest way to embed metacognition into your courses is to have students describe their learning process to you and their classmates. Have them speak to which skills come easy to them and which ones are a struggle to learn. Have them log how much time they spend completing specific tasks for studying or completing an assignment, describe what those learning tasks were, and why they chose those methods instead of others.

From there, you can give them the resources they need to support their learning. View your experience as an expert as resource; talk to them about your learning process: how do you efficiently read academic papers? What do you do when you get tired, distracted, or frustrated in your work? What are your pitfalls? Do you grab your phone? Do you take a break? What effective learning or productivity strategies do you turn to when your work gets hard?

If you’re not comfortable with this much vulnerability, embed a resource on metacognition in week one of two for students to discuss.

Any Sandy McGuire video on YouTube is a good place to start, like the one below.

You can show students a portion of the video or give them timestamps for a specific section that highlights a set of practices you want them to consider. You could then ask questions like, “Which of these practices seem most helpful?”, “What makes these strategies hard to implement?”, and, “What can you, your classmates, and I do to remove those barriers?”

Students cheat because they think the problem in front of them is too big to overcome on their own. The more tools we have to help students navigate the inevitable difficulty of learning, the smaller those problems become.

Looking for someone to teach metacognitive skills to your students? I’ve got some strategies, and I’m ready to share em’! Click the button below to inquire about workshops and keynotes for your students.