Problem-Centered Careers: A Framework for Vocational Identity Development

Don't do what you love—eradicate the things you hate instead.

This is the second piece in a two-part series about helping students—and adults—cultivate meaningful careers. Feel free to check out part 1 below, which describes the impetus for this methodology.

How We Should Talk to Young People About Career Choices

Nearly 4 million US high schoolers will walk across the stage this month, turning their tassels from right to left and entering an increasingly uncertain job market. With college enrollment rates still climbing out of pandemic lows, and scrutiny about higher ed’s

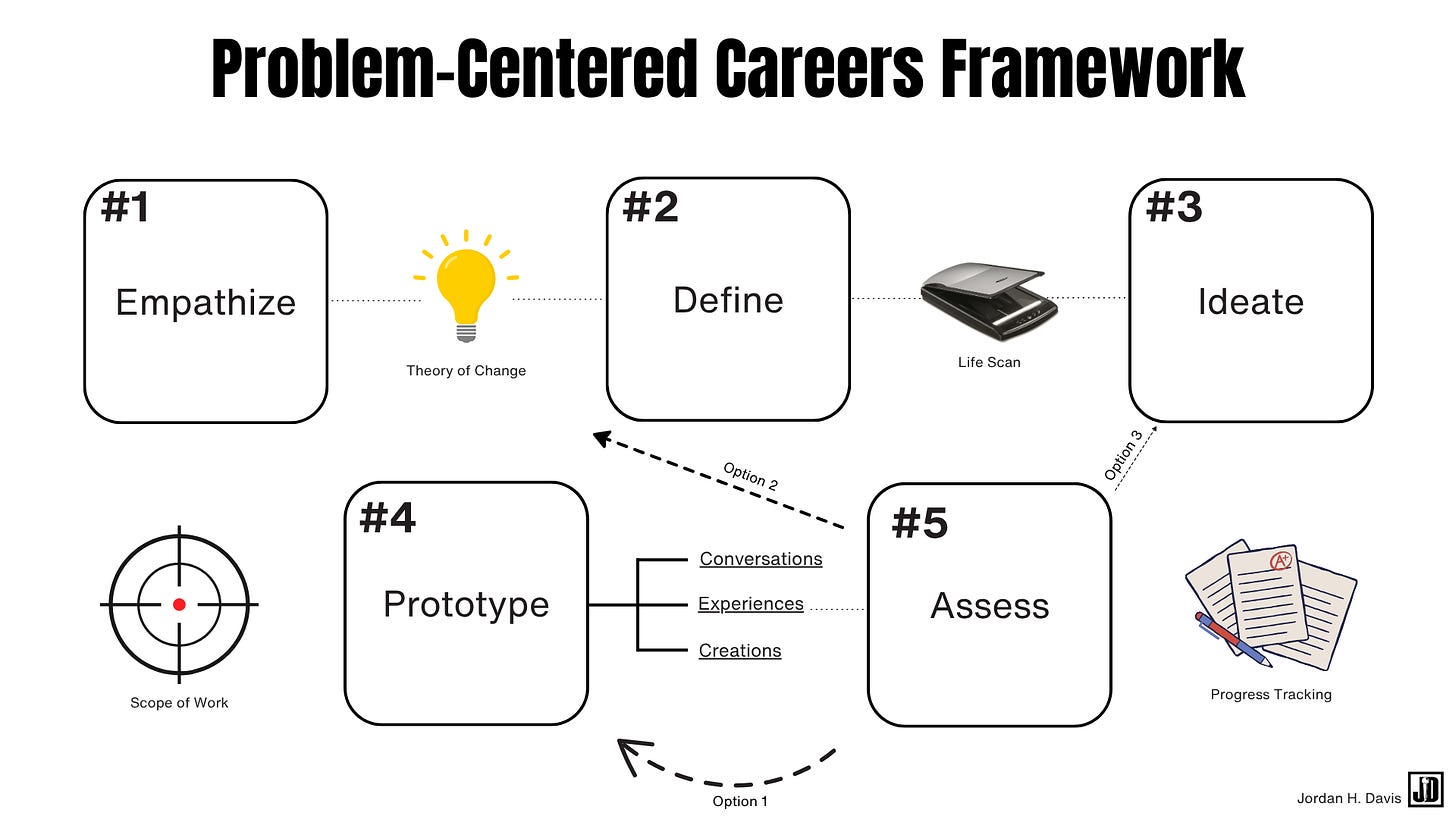

Problem-Centered Careers Framework

The Problem-Centered Careers Framework (PCC) is a career decision-making methodology that infuses design thinking, problem-centered design, and social impact innovation into a tool used to cultivate purpose, joy, and sustainability in one’s career. While PCC fosters the same flourishing-centered outcomes as constructivist career theories, its most defining characteristic is that it recognizes all careers as problem-solving endeavors, even those commonly seen as yielding minimal societal consequence.

A departure from the job-skill fit emphasized in traditional vocational development frameworks, PCC starts not with one’s credentials or professional talents, but with the problems they desire to solve in the world, whether local, regional, national, or global. This problem-solving approach invokes purposeful work, which data show leads to increased workplace satisfaction, physical and mental wellbeing, and an overall sense of life fulfillment.

By starting with problems to solve instead of jobs we’re qualified to do, we discover more pathways and creative career combinations, embracing a growth mindset that assumes anyone can develop whatever skills their chosen problems require. The framework’s nuance helps tackle the wicked problem of figuring out how to balance one’s career success with their physical, mental, social, and financial wellbeing. PCC helps its users view these dimensions of wellness as self-defining and mutually occurring, allowing people to claim greater agency over the wellness goals they set in these various dimensions.

The methodology is tailor-made for the classroom, and aims to equip career counselors, educators, and students themselves to design career paths that don't require compromising their values. This article outlines this process in detail.

Goals of PCCD

Problem-Centered Career Design tackles three core career challenges: getting untangled, finding meaningful work, and creating work-life balance. I will explain these three points in order.

Getting Untangled

There are many ways to define professional stagnation. An 11th grader is encouraged to start thinking about life after high school, but doesn’t know where to start. A 19-year-old college sophomore has to declare a major in the coming spring semester, and finds themselves stuck between political science, sociology, and international relations, which all seem equally appealing. A 25-year-old marketing coordinator's first job out of college isn't as creative or meaningful as they’d imagined, and even the managerial positions above them don’t seem to be much of an improvement. A 34-year-old high school teacher desperately wants a career pivot after years of burnout, struggling to rekindle the passion they once had for teaching. With one kid off to college and another to trade school, a 46-year-old mechanic shop owner wants a new professional challenge without sacrificing their earnings. A 58-year-old retired corporate attorney wants to increase their earnings without taking on a demanding executive position or joining the consulting grind.

These microscenarios highlight moments of “tangledness” we experience in our lives—times where we face apathy, overwhelm, exhaustion, boredom, and financial and logistical restraints that feel insurmountable without making a career change. We’re often steered toward the “common sense” choices: the higher-paying job that we can’t refuse, the role that ‘makes the most sense’ for our professional trajectory, the path on which we’re least likely to fail, etc. Although these choices sometimes turn out to be good, PCC challenges the way we arrive at these decisions. Instead of making fear-based decisions (fear of failure, judgment, the unknown), PCC helps people plan their vocational path by factoring purpose, joy, and sustainability into the equation without sacrificing one for the others.

Finding Meaningful Work

A 2017 survey of nearly 5,000 adults asked an open-ended question about what brings meaning to their lives. While “family” topped the list at 69%, “career” came in second at 34%, suggesting that work plays a significant role in how people create meaning. Problem-Centered Careers is concerned with meaning-making as opposed to meaning-finding, as one’s values, knowledge base, and lived experiences shape how they see themselves in connection to their work. The first goal that PCC users establish is their goal for society at large. They then reflect on their personal and professional goals and seek out work opportunities that align with those goals.

Creating Work-Life Balance

Work-life balance is hard to achieve, and the world’s workers want more of it. Of the 26,000 survey respondents in Randstad’s multinational survey on workplace views and attitudes, work-life balance is now tied with job security as the highest-ranking factor for talent when considering their current or a future job—83% found these two factors important, while 82% found pay important, the first time in the study’s history that work-life balance surpassed pay.

The Problem-Centered Careers framework sees work-life balance as both a human right and a requirement for effective problem-solving. PCC positions personal wellbeing as a gravity problem: a non-negotiable priority that can’t be compromised. Though learners are encouraged not to waver on their commitment to their wellbeing, wellness is defined holistically, and users of this methodology can prioritize different aspects of their wellbeing to match the ebbs and flows of life. The goal is to eliminate the false binary that pits financial security against physical and mental health.

What PCC Doesn’t Do

Problem-Centered Careers does not suggest that some careers are more meaningful than others. For example, if a high school student identifies bad pizza as a problem they want to solve, this seemingly simple concern can lead to multiple meaningful career pathways. They might become a chef or restaurant owner, bringing joy and cultural learning experiences to people who enjoy their recipes. They could pursue food criticism, helping people identify quality pizza and the best restaurants that serve it. They might focus on increasing access to vegetables in food deserts, allowing low-income families to make fresh pizza at home. Each pathway addresses the same core problem through a different professional lens, demonstrating that all issues are social issues worth solving, no matter how trivial they may seem.

PCC does not promise life transformations, although it may spark initial steps toward big life changes. Many who use this framework will make marginal changes to their personal and professional lives.

Lastly, PCC does not take the place of mental health counseling and career counseling. This framework is meant to be used by counselors to support, not replace, their counseling strategies. It is also a framework that anyone can use before, during, or after counseling. Individuals suffering from depression, anxiety, or other clinical conditions should seek professional help.

The Process + How to Use

The following section outlines the Problem-Centered Career Framework from the perspective of the student/learner. I urge anyone using this tool to embrace deep reflection, daydreaming, rabbit holes, and crappy first drafts this methodology demands.

Empathize

Answer the following prompts in as little or ample detail as you find helpful, while knowing that more thorough responses may lead to clearer, more honest revelations.

Prompt 1: What do you hope to gain from using this framework?

Keep this answer top of mind as you move through PCC.

Next, respond to Prompt 2 below.

Prompt 2: If you could instantly solve a social problem at the snap of a finger, without worrying about money or public perception, what would that problem be? This problem can be local, regional, national, or international in scope.

Once you have your answer to Prompt 2, come up with a second and third answer. Rank these answers in order from most to least important to you.

If you have trouble coming up with three problems, use Prompt 2b below.

Prompt 2b: What have you seen recently—on the news, on social media, or in your personal life—that’s made you angry or upset? Name a sudden or developing event that connects to an issue that others may be experiencing.

Lastly, answer Prompts 3 and 4 below for each problem you’ve listed. It may help to create a separate document or workspace for each problem to focus your thinking:

Prompt 3: How would you go about solving the problem? Briefly name the policies, funding mechanisms, initiatives, resources and cultural shifts that need to be in place in order to solve the problem in the real world.

Prompt 4: How would you know when the problem has been solved?

You should now have three documents, each containing paragraphs that respond to questions about the three different problems you identified in Prompt 1. Put these paragraphs together to form a cohesive narrative. These narratives—also known as theories of change—contain a detailed description of the problem, potential solutions, and a vision for what an ideal future looks like. These narratives are the foundation for the three career paths you’ll explore as you move through the methodology.

Define

This step helps you define your personal and professional goals by conducting a detailed examination of different aspects of your life. You’ll also make the distinction between what you’re good at and what you like to do, the goal being to pursue professional avenues that require skills that involve both pleasure and proficiency.

Life Scan

Rate each bulleted item below on a scale from 1-10, with 10 being the most fulfilled you could be. Then, set a goal score for each item. For example, I may rate my sense of adventure at a 5, but only aspire to raise it to a 7, acknowledging that there are areas of my life that I’m more willing to maximize. Write a one-to-two-sentence explanation of why you gave your rating for each item.

Romantic Partnership - My romantic desires are being met, whether solo or with others.

Friendships - I have loving, mutually-beneficial platonic relationships with people who share my interests and with whom I spend adequate time.

Adventures - I’m engaging in activities outside my comfort zone that are exciting, challenging, and rewarding.

Environment - I experience consistent safety and belongingness in the daily environments in which I spend the most time (home, work, college campus, etc.).

Health & Fitness - My physical, mental, and emotional wellbeing are all at a sustainable level, and I feel good inside my body as a result.

Learning - I'm consistently growing my knowledge and skills in areas that matter to me.

Spirituality - I have a sense of connection to something greater than myself that provides comfort and clarity during difficult times.

Financial Wellbeing - I have enough money to meet my needs without constant financial stress.

Creativity - I regularly engage in creative expression that feels fulfilling, whether through art or problem-solving.

Family Life - My relationships with family members (chosen or biological) are healthy, supportive, and contribute positively to my overall wellbeing.

Community - I feel connected to and contribute meaningfully to groups or causes beyond my immediate circle, creating a sense of belonging and shared purpose.

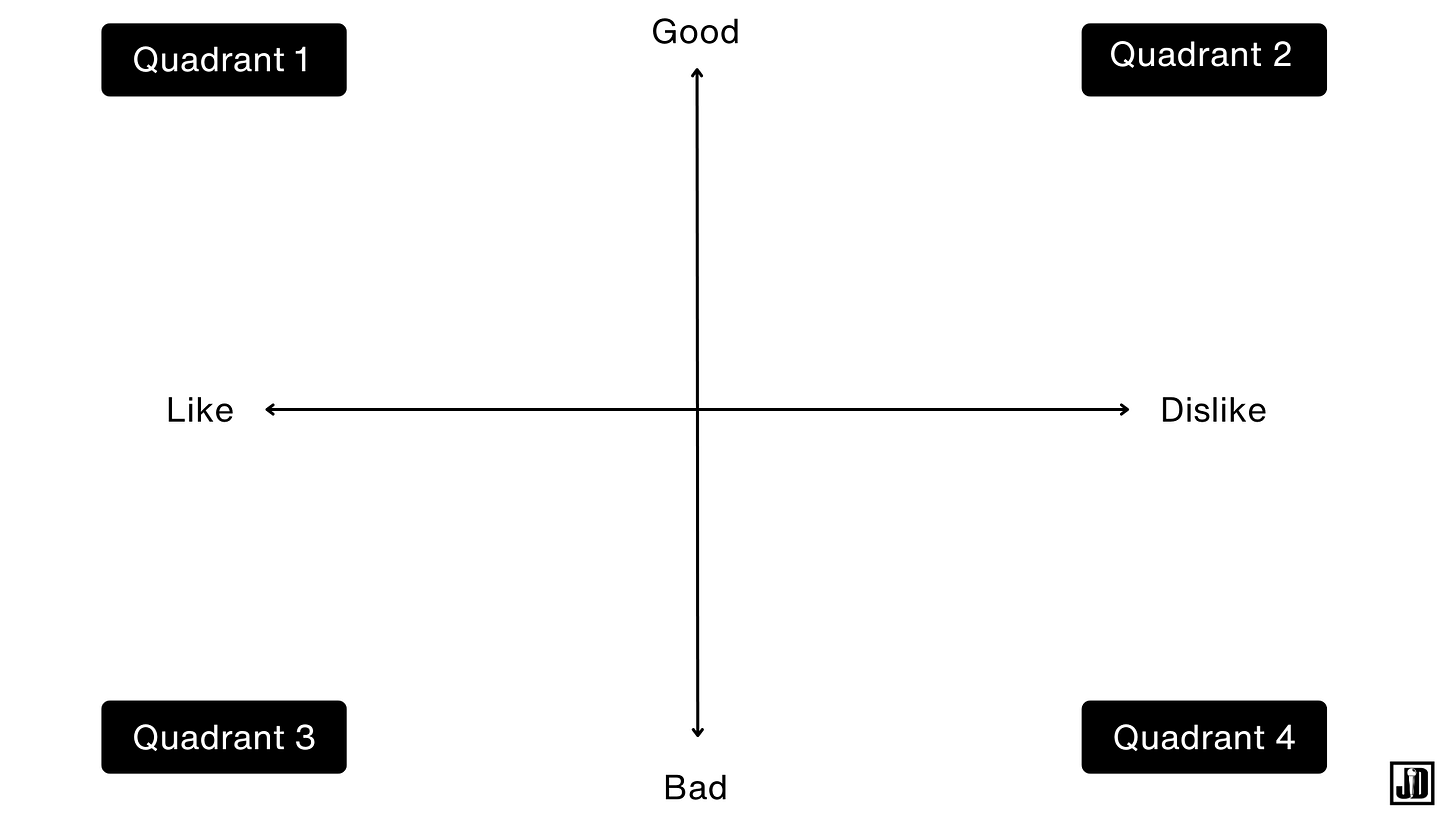

Skills Inventory

Create the above matrix in your notes. Think of as many academic and professional skills as you can and plot those skills on the matrix. Save this matrix. Ask a close friend or family member to confirm the accuracy of your matrix. As you design your career, prioritize professional roles that require the use of quad 1 and quad 3 skills. As you identify skills used by professionals in your desired field, add those skills to the matrix.

Ideate

In the ideation step, you’ll identify job roles that align with the goals you set in the “define” step.

Respond to the following prompt in your notes:

Prompt 5: Why hasn’t this problem been solved before?

Prompt 6: How have people tried to solve the problem in the past?

Your responses should reveal real people who have job titles: data analyst, flight attendant, mayor, yoga instructor, professor, etc. Make a list of all the relevant stakeholders. From this list, pick at least three job roles in which the work aligns with your theory of change.

Write Your Ideal Scope of Work

Use your theory of change, the skills listed in quadrants 1 and 3 of the skills inventory, and the goals from your life scan to write your ideal scope of work. Think of your scope of work as a hybrid between a job description and a resume—it details how you spend your working hours across all of your professional endeavours.

Use the three job roles identified at the beginning of the ideate step as the foundation for your scope of work. Your scope of work should list the number of total hours you’d work each week, the number of hours spent on each role, and what that work would entail.

Through this activity, you’ll find that it may be feasible, even ideal, to work multiple jobs to reach your desired personal, financial, and professional goals. The prototype step below will put your design to the test!

Prototype

Now, it’s time to take action on the professional life you’ve designed. There are three main ways to do this: prototype conversations, prototype experiences, and prototype creations.

Prototype Conversations

Prototype conversations are discussions you have with someone who’s doing work you’re interested in. The goal is to see whether your conception of your professional life is possible by learning from people who are on a similar path. It might help to find people who have similar identity characteristics, such as race, gender, age, or socioeconomic background.

These conversations can answer questions about work-life balance, help refine your long-term goals, and illuminate systemic barriers that people face while trying to solve the problem. It can even help you realize that you’re no longer interested in this path, and that you should change your focus. In this case, you may need to draft another scope of work that includes a different set of job titles and skills, or you may want to explore your second or third narrative developed during the empathize step.

Volume is the keyword to landing prototype conversations. Sending a generic message to three people won’t be enough. The more invitations you send, the more likely you are to get a response. Cast a wide net, lead with curiosity, and offer to buy the person coffee if you can. People are busy, but they’re usually more than willing to share their success story with others.

Prototype Experiences

Prototype experiences provide opportunities to practice applying your scope of work. Examples of prototype experiences include:

Attending a hands-on workshop at your local community center

Signing up for an amateur competition (business pitch, baking, art, etc.)

Sitting in on a college lecture (Yes, this is possible—visit your local college’s website, search for courses connected to your problem, email the professor, and ask to sit in on a lecture.)

Completing an internship

Applying for a job you feel underqualified for (to experience how it feels to apply for the job, to fully understand the application process, etc.)

Attending a free webinar

Taking an online course

Applying for a mentorship program

Studying abroad (Most colleges offer year-long, semester-long, and month-long study abroad experiences.)

You’ll start to see a cyclical relationship between your prototype conversations and your prototype experiences—the conversations you have will present prototype experiences, and you’ll find more interesting people to talk to as you complete the experiences.

Prototype Creations

Prototype creations are opportunities to fulfill the scope that you create yourself. Examples of prototype creations include:

Creating a Substack and writing weekly articles about your subject

Launching a website to house your ideas or run your business from

Starting a podcast

Writing a song or a short film

Building software (apps, video games, etc.)

Building hardware (3D models, robots, pottery, etc.)

There may not be a dream job out there that combines your skills, problems, interest areas, and personal goals; you may need to carve out a space for your ideas if it doesn’t exist yet.

Assess

Spend a few months exploring one of your three narratives. Revisit the life scan document every 30 days and check on your progress toward your goals. Even if one of your high-priority scores doesn't move much from one month to the next, your efforts on this new path might raise your score in other unexpected areas.

After you do some honest assessment, you can:

Scale Up - If you’re making good progress toward your goals, scale up your prototype so that it becomes sustainable.

Choose a Different Prototype - Choose a different prototype to try solving the problem from a different angle, or to answer questions that your previous prototype didn’t answer.

Do More Ideating - Make some tweaks to your scope of work to better align the work with your problem, skills, goals, and/or areas of interest.

Explore a New Theory of Change - Go back to the define step and choose a new path altogether.

Start From the Beginning - Either you’ll uncover a fresh problem to pursue, or you’ll realize that your not yet ready to let your current problems/theories go.

Pay attention to how you feel at every checkpoint. If pride, accomplishment, inspiration, and curiosity are the dominating feelings, then it’s worth pressing forward on your current path. If you feel stagnant, uninspired, or like your scores are lowering in ways you feel viscerally, it may be worth pivoting to your second or third narrative for a few months. If you really want to get creative, try combining narratives. For example, a Digital Marketing Manager for a climate justice nonprofit tries their hand at standup on the side. They do shows at local bars, bringing joy to audiences using the same storytelling skills and unique worldview that make them effective at their full-time job.

In addition to reflecting on your life scan, simply ask yourself, “Am I making progress toward the solution that I’ve set out to create?” Typically, your professional success would indicate that you’re proficient at solving the societal problem you’ve chosen. However, you could find that you’re getting promotions and achieving greater work-life balance without reaching your desired level of social impact. Be wary of how people perceive your new journey, positively or negatively. Don’t try to feel how you think you should feel about your career—just feel, be honest about what you notice, and be brave enough to tweak your approach when things don’t feel right.

It’s difficult—yet possible—to teach a framework that you haven’t used. I highly encourage any educator who’s considering embedding this framework into the courses to tinker with it themselves, either before or while using it with students. You’ll understand your triggers, points where you get tangled, and ways to make the model more conducive to how you think, all of which will give you ideas for integrating this framework into your teaching.

I’m inspired by Burnett and Evan’s story about how their Design Your Life Framework came to be: after running a prototype of their now-established DYL course at Stanford, one student from that initial weekend session said, “No, we are not done yet. This is important stuff and you don’t understand. We have no place to have this conversation!!”

Students long for this type of critical reflection about their careers. This is the ultimate way to connect what students are learning to their lives outside the classroom, the type of connections that change lives. Let’s make more of those connections.

If you’ve made it this far, thank you. I kindly ask that you share this piece with people who’ll find it just as valuable as you did. Add your two cents while you’re at it.

If you enjoyed this piece, you’ll also enjoy: