One Key Parenting Skill That Translates to Good Teaching

Intergenerational empathy is a proven trait of good parenting. Here's how it translates to good teaching.

As a 25-year-old man with no kids, I hesitate to draw parallels between parenting and teaching. But I found one parenting study conducted at the University of Virginia that addressed a nagging challenge often expressed by the deans, directors, and organizational leaders that I speak with.

In 1998, UVA researchers began a longitudinal study to understand how empathy is passed down through generations. Each year, they videotaped conversations between teenagers and their moms and teenagers and their best friends about a personal problem. The researchers observed empathic behaviors from the conversants, like offering instrumental help (e.g., suggesting study help), providing emotional comfort (e.g., saying "it's okay"), and accurately reflecting the teen's problems.

The study found that teens who experienced empathy from their mothers at 13 were more likely to show empathy in their friendships between ages 13 and 19. The teens’ peer empathy subsequently predicted their supportive parenting behaviors ten years later, suggesting an intergenerational transmission of empathy.

That last finding leads me to speculate that students who experience empathy from their teachers and close friends are not only prone to employ empathy in their current personal relationships, but they’re more likely to do so in their professional roles. This study gave me the language to describe the one skill that resistant, traditionalist faculty struggle to apply.

Intergenerational empathy is the ability to understand and relate to people of different ages. It can be practiced through deep listening and being open and curious about the words and phrases that young people use, the cultural references they make, the values they uphold, and where they derive those values.

When event organizers request me to speak, nearly all of them raise a chief concern: the generational divide between their students and their teaching staff. All of them see this inability to relate to and value the experiences of their students as a barrier to improving teaching and school culture.

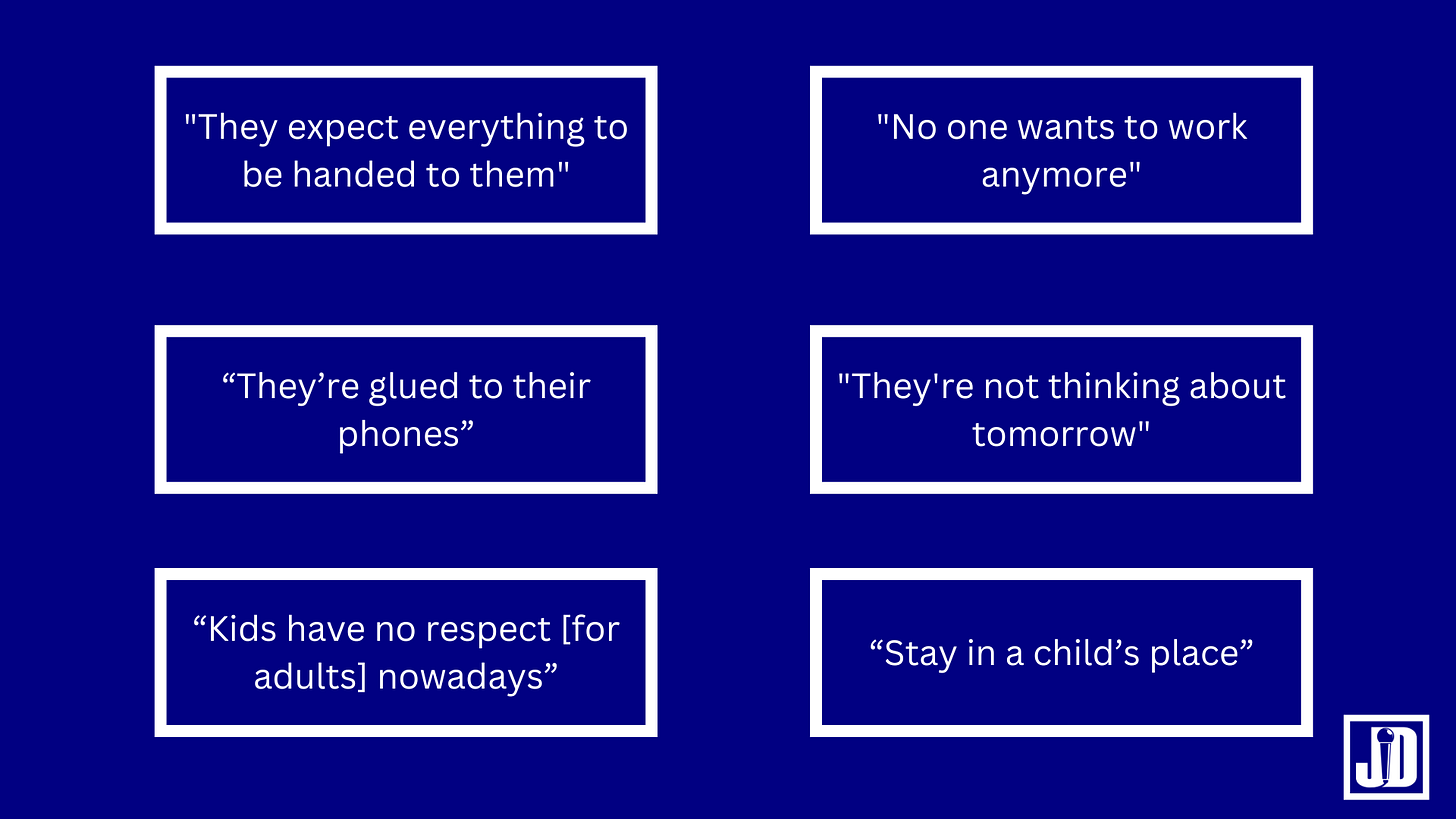

Do any of the above phrases sound familiar? Have you said any of these yourself?

These are the idioms that school leaders routinely ask me to scrub from their educators’ vocabularies. These phrases evoke the conclusion that many educators draw about today’s students: kids are entitled and needy, and this entitledness and neediness are getting in the way of my goals. And, according to these faculty, this display of entitlement and neediness are negative symptoms of Gen Z, a group of 13 to 28-year-olds that grew up in an era where instant gratification machines were placed in their hands during their most formative years.

This mindset prevents educators from exhibiting empathic behaviors toward students that are foundational to inclusive teaching. Why would an educator redesign an assignment to make it more inclusive—and more rigorous for all students—when they view demands for inclusive assignments as entitled and needy?

So…how do we practice (and encourage educators to practice) intergenerational empathy?

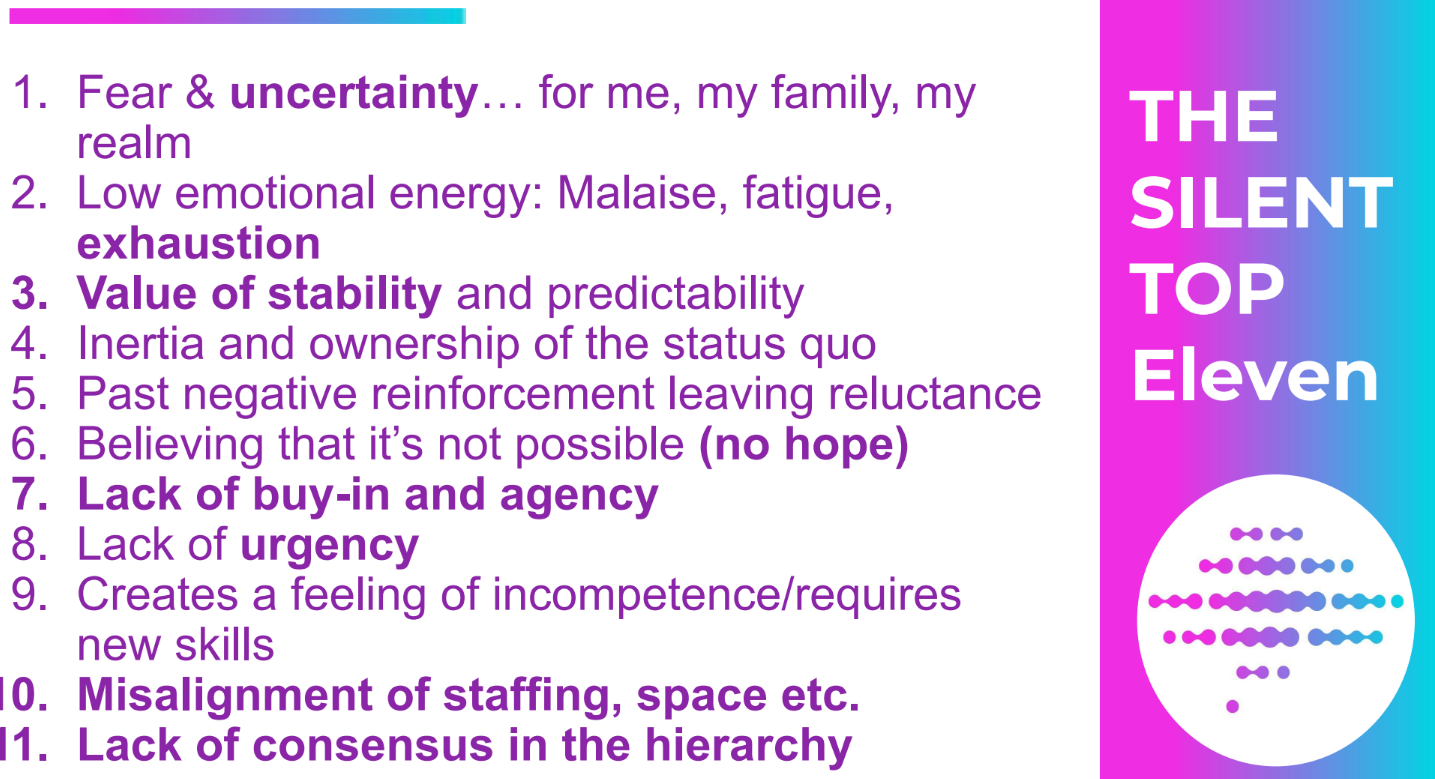

The above PowerPoint slide created by the Council for Independent Colleges shows a list of unspoken reasons why employees in any industry resist change. When getting resisters to embrace AI in the workplace, for example, you might hear them say, “there’s no time to learn the tools”, or, “it’ll never work because there’s not enough money to ensure access for everyone.” But these pragmatic responses belie the real reason they’re opposed to change; they fear what change will mean for them.

The first step in helping faculty overcome the barriers above is to help them get rid of their delusion—they do struggle with one or multiple of the challenges above, and that doesn’t make them a bad person or a bad educator. You can’t solve a problem that you’re unwilling to acknowledge. Admitting that they’re struggling is counter to their ingrained sense of independence. It’s also hard to get someone to confess that they’re struggling if they don’t believe the person on the receiving end can do anything about it.

This poses a unique challenge for all educational institutions. How can universities, school districts, and state departments of education ensure that faculty feel supported in these deeply personal areas? Continuing with the status quo because of our unwillingness to face these deeper challenges is not an option.

Why Intergenerational Empathy Feels Impossible

Just like it’s possible to teach a course that’s both care-filled and academically rigorous, it’s possible to be a student-centered educator without being burned out or giving unilateral power to your students. Teachers who understand this build the capacity to empathize with young people from whom their values, lifestyles, and ways of communicating differ vastly.

But it takes time and energy to deploy empathy, two things that educators already feel low on. Those who have the capacity to be empathetic parents—and faculty—are often privileged in some way. The well-paid full-time tenured professor teaching three courses per semester has more bandwidth for empathy than the adjunct teaching 8 courses across 3 institutions, just like the stay-at-home parent has more bandwidth to empathize with their children than the parent who only has an hour with their kids each day after coming home from working multiple jobs.

Additionally, the burden of emotional labor is often placed on women, who make up the majority of the teaching force and who are seen as caregivers both at home and in the classroom, a label that male educators are seldom given.

Holding these truths can be overwhelming. But doing so models the rigor that educators expect of their students. Remember, we have the fully formed brains in the room. Modeling empathy for students gives them the tools to model it back to us and among their peers.

Linked below is a clip of a recent keynote that I gave to the PSRP chapter of the Baltimore Teacher’s Union. This was a group of about 300 non-teaching staff members from Baltimore City Public Schools, and the message was made to apply to anyone in and around education: parents, accountants, school resources officers, custodians, administrative personnel, teachers and everyone in between.

Looking for a keynote speaker for your next event? Visit my website below to bring this message or others to your audience.

If you enjoyed this post, you might also like: