How We Should Talk to Young People About Career Choices

With shrinking trust in higher ed and the exponential growth of career options, we need to change the conversation about life after graduation.

Nearly 4 million US high schoolers will walk across the stage this month, turning their tassels from right to left and entering an increasingly uncertain job market. With college enrollment rates still climbing out of pandemic lows, and scrutiny about higher ed’s value mounting each day, state education departments across the country are pouring more money into career and technical education (CTE) initiatives. In a 2024 Education Week Survey of 868 teachers, school leaders, and district staff, 62 percent said their district offers more CTE courses now than 10 years ago.

Even as schools explore ways to put as many options in front of students as possible, there’s less talk about how we’re helping students navigate the murky waters of life after high school. Most young people are living at home longer, increasing their families' influence over career decisions. This pressure manifests in several ways: young people skip valuable internships because they need immediate income to support their families; those from low-income households feel obligated to prioritize high-paying careers over their interests; and some parents threaten to withdraw financial support toward degree programs that aren’t in STEM, law, or business.

My insights on these issues were deepened back in 2023, when I was invited to give a keynote at an international conference in Atlanta. 13,000 middle and high school students from around the globe filled the Georgia World Congress Center for the 2023 Future Business Leaders of America (FBLA) National Leadership Conference. Eager, formally-dressed teenagers from the US, Canada, and China converged on the southern metropolis to compete in business-themed events for scholarships, awards, and professional development.

My 20-minute talk introduced students to design thinking, an innovation methodology traditionally used to develop products and services in business and education. But I wasn’t there to talk about entreprenership—I was there to give them a framework for addressing one of the greatest challenges they’ll face: designing their lives after graduation.

I was introduced to design thinking as a first-year master’s student studying Learning, Design, & Technology. We mostly used it in concert with Universal Design for Learning (UDL) to build courses, where instead of designing instruction based on our expertise or that of a content expert, we designed courses that centered the diverse interests of students. In all levels of education, students’ needs quickly get washed away when deadlines, bureaucracies, ego, and resource constraints come into play. Design thinking was a way to ensure these challenges didn’t quell the creativity necessary to make student-centered learning possible.

I began to experiment with design thinking’s use in career navigation. I often found myself in front of students who wondered how they should plan their lives after graduation—“Is college a wise investment?”, “What major should I choose?”, “How do I land a ‘good’ internship in my field?” After months of tinkering, I concluded that if students set out to find opportunities to build solutions to problems they cared about, and were given tools to Frankenstein a sustainable life around those pursuits, such a perspective would ease their physical, emotional, and psychological distress. To say that a 3-day conference with over 13,000 students was a prime opportunity to test this hypothesis is an understand—I had the ear of our future world leaders, and the potential to influence how they see the world as well as their role in it.

The students I met while in ATL were remarkable, possessing a critical optimism about their future that inspired me. Meanwhile, so many were battling copious amounts of career-related stress. They wondered whether to chase their passion or follow the money, a false binary they felt plagued by. They feared that sleeping in libraries, shelving their social lives until their first job offer, and coping with debilitating depression every December and May during finals week was the norm for successful students. Although my keynote proved to be helpful, it was at that conference that I learned about the barriers to their academic and professional flourishing that design thinking alone couldn’t reach. The methodology begged for more nuance and scaffolding.

The Bad Advice We Give to Graduating Seniors

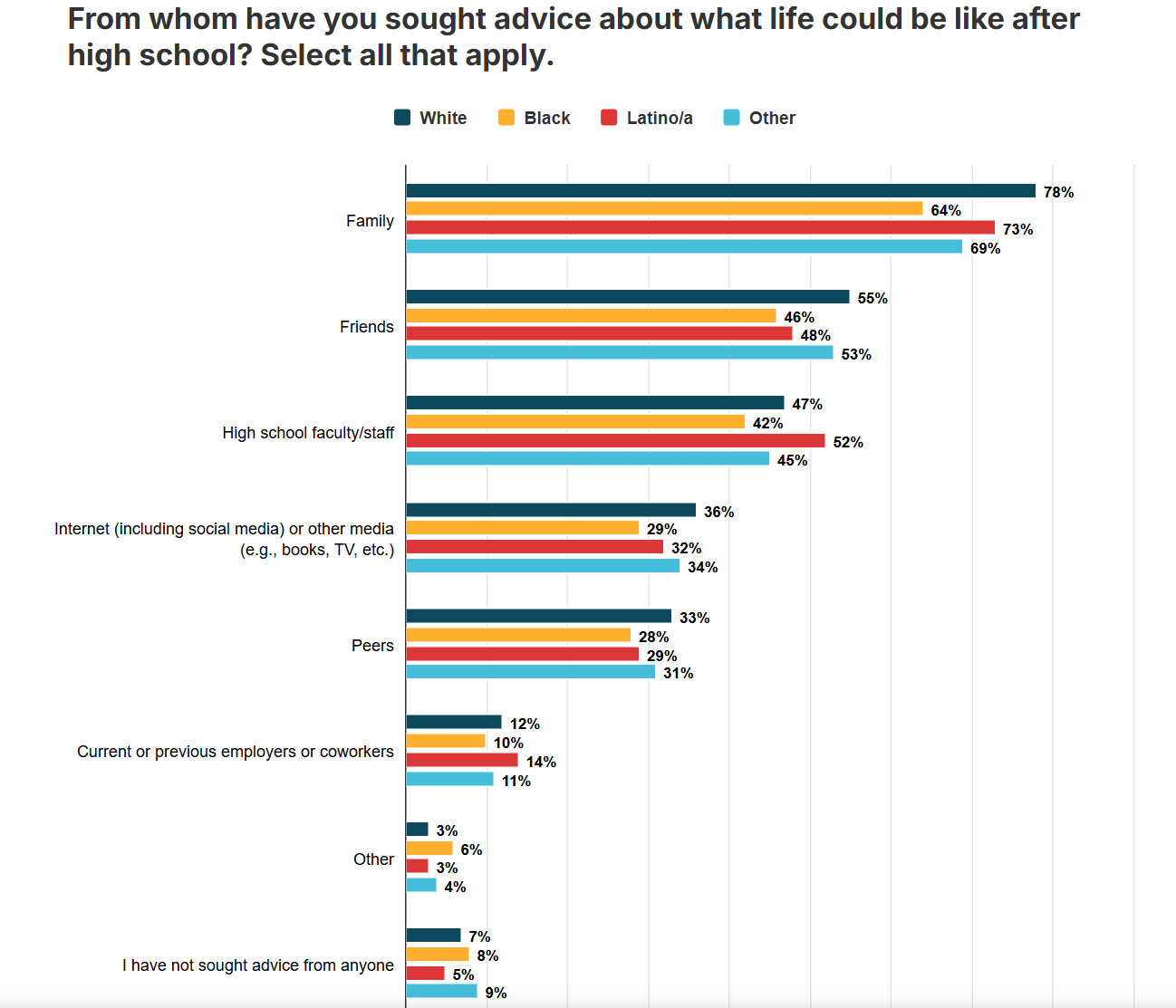

Millions of young people receive career advice from their loved ones. A 2022 Best Colleges survey found that high schoolers received more advice from family and friends than anyone else. That advice might sound something like this:

Great at math? Pursue a career in STEM. Gifted writer? Become a journalist or public affairs professional (because freelance writers don’t make any money). Talented artist? How about teaching art in the local public school district (to avoid becoming a “starving artist”)? Were your parents successful lawyers or business professionals? Follow in their footsteps and use their connections to get ahead. Good with your hands? Pick up a trade; bonus: you’ll complete the credential in half the time and at a fraction of the cost compared to your college-going peers. If you’re not a high achiever and you don’t have a burning passion for a line of work, go to community college and see if something sticks. And if none of this sounds appealing, do a few years in the military and enjoy the financial perks. Make a LinkedIn profile. Network to no end. Create a side hustle to stay afloat. And if you find a job you love, you’ve struck gold!

If you’ve received at least one of these recommendations from a friend or family member, you’re not alone. Any prescriptive advice along these lines strips young people of their agency to pursue careers that align with their values, interests, and desired lifestyle. It also leaves students ill-equiped to combat threats to their professional flourishing: the FOMO and overinflated expectations created by social media, the patriarchal and politicized lens through which they’ve been presented career options, the grief experienced after being rejected from their life-long dream college, the trauma of having their value as a son or daughter be quantified by the sum of their achievements, and academic burnout, which, if unaddressed, can metastasize into early professional burnout.

This isn’t just a ‘young people’ problem. Gallup’s 2024 Global State of the Workforce Report, which shares results from an annual survey consisting of nearly 140,000 respondents representing 140 countries, shows that according to the popular 8-item Flourishing Scale, 58% of the world’s workforce is struggling, while 8% are suffering in their careers.

This is why career counseling requires a master’s degree, and why constructivist theories like Social Cognitive Career Theory, Chaos Theory of Careers, and Super’s Life Span Life Space Theory have become foundational theories in career counseling education in recent years. Constructivist approaches frame career navigation as a non-linear, collaborative, and life-long discovery process, all of which I thought were key principles to highlight in the framework I was developing for my work with students.

“Life Design” as an Emerging Trend

I was pleased to know I wasn’t the only one retrofitting design thinking to career navigation. Bill Burnett and Dave Evans, who co-teach the popular “Design Your Life” course at Stanford University, developed the Design Your Life framework, which helps people of all ages set and pursue their life goals. Since publishing their 2016 best-selling book, universities like Harvard, Southern New Hampshire University, and UC Berkeley have used the framework in courses and training on career development.

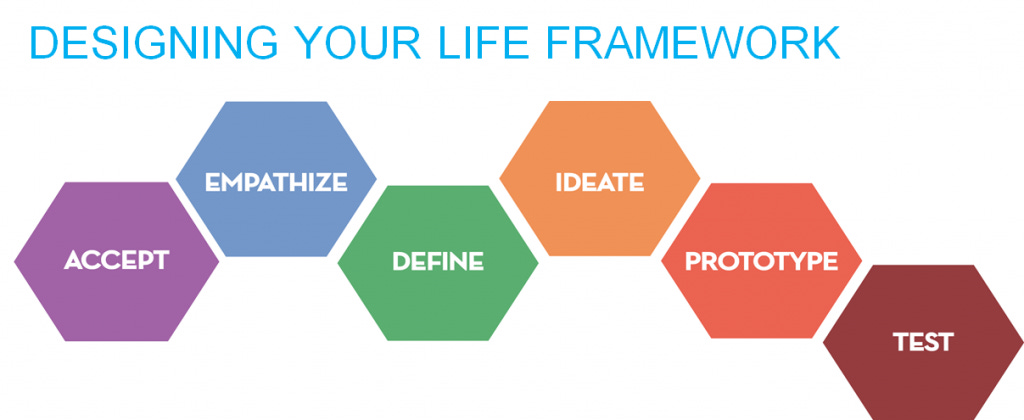

In Burnett’s 2017 TEDx Talk, he presents several ideas grounded in design thinking. Here is a consolidated version of these steps:

Accept: You can’t solve a problem you’re not willing to have. There are problems that we shouldn’t have; these are the ones over which we lack control—bad bosses, bad teachers, the cost of college, where we grew up, etc.—but many of us still stress over. Once you identify one of these problems, which Burnett calls a “gravity problem”, quickly determine whether you’re willing to work within that problem or whether you need to relocate to where the problem doesn’t exist. The quicker we accept gravity problems, the quicker we can design our lives by focusing on the things we can control.

Empathize: Your life’s construction should align with your goals. The values that undergird those goals will guide your thinking. In order to excavate those values, ask yourself questions like, "Why do I work?”, “What's it for?”, and, “What's work in service of?”

Define & Ideate: If you could envision an alternate version of yourself, living a life completely different from the one you’re living now, how many versions of you could you come up with? Each person has multiple happy versions of themselves that they could live. Earnestly mapping out three of those versions (no more, no less) is a helpful process for generating a new set of personal and professional goals.

The three versions he instructs us to map: 1) Your current life, 2) the life you’d live if your current life no longer existed, and 3) the wildcard life, the one you would live if money or image weren’t a factor.

Prototype & Test: Prototype conversations and prototype experiences are two ways to ‘test out’ those lives. Prototype conversations involved talking to people who are living out the versions you’re interested in exploring, while prototype experiences can take many forms, ranging from an internship to sitting in on a lecture at your local college. Designers must reflect on whether the prototype is viable and scalable, determined partly by the prototype’s alignment with the values and goals defined earlier in the design thinking process. Designers must also be careful not to agonize over decisions they make. Effective designers know they won’t get every decision right, so they learn from them, let go, and keep designing.

Reflecting on Burnett and Evans’ work unveiled the missing pieces that I hope to fill when presenting this framework to students. First, instead of developing a theory of work, I challenge students to develop a theory of change. I ask them questions like, “If you could solve any problem in the world—whether local, regional, national, or international—what would you solve, and why?” I feature social justice and social problem-solving heavily when I introduce design thinking to students. I want my learners to develop a service-led, de-centered perspective on how their work will impact others, and the three “versions” they map out are based less on the lifestyles they want to live and more about various roles they could play in making their theory of change come to fruition.

Secondly, instead of focusing on what it takes to ‘let go’ of the design decisions they make, I use a trauma-informed approach to help students understand why it’s hard for them to let go of their decisions. Fear of failure, lack of control, and previous relational dynamics in which they’ve experienced abuse from their superiors are often the root causes of their distressed decision-making. If students can better understand how those traumas took root, perhaps they can claim agency over them and engage in the slow work of healing from them. Just like educators don’t have to be therapists to implement trauma-informed teaching practices, you don’t need to be a psychologist to help students identify the source of their career stress.

My hope is that design thinking becomes both a go-to methodology for career development and a mindset that’s woven into the fabric of K-12 and higher education. Along with giving learners tools to creatively craft their careers in alignment with their values and desired lifestyle, design thinking challenges common assumptions about why people undergo career pivots and to what ends. It validates those who want to add, adjust, or remove aspects of their careers because their fundamental views on the world have changed in a way that no longer agrees with their work. It affirms people who make academic and professional career decisions because they’re bored, burned out, or yearning for human connection. It dismantles the assumption that the best career decisions are the ones that lead to the highest position with the highest salary.

I hope the principles expressed throughout this article become central to conversations between young people and their parents, educators, and dear friends to whom they turn for career advice. I hope that reframing, mindfulness of process, curiosity, radical collaboration, and bias toward action underpin every career and technical education curriculum. A career development framework grounded in design thinking and integrated into class assignments, projects, activities, and discussion posts is the next step for the educator looking to better prepare students for life beyond their classroom. I hope students themselves, as they stare at their Common App portal, sleep deprived, mulling over whether this is all worth it, develop the instinct of starting a note in their Notes app where they can reflect on prompts aligned with this methodology to bring them short-term clarity.

I’ve been toiling with this framework since 2023—a dream career development methodology that builds on Design Your Life by infusing problem-centered design, trauma-informed care, and social impact innovation to help people traverse a job market filled with so many unknowns. I’ve built it. It has a name. It has graphics. It will be the next thing you see from me in your inbox.

In the meantime, let me know what you think about this piece below. What questions, objections, and “ah-ha!” moments did it raise for you? Discuss below!