How to Make Your Lectures Addictive

As screens and apps compete for students' attention, here's what we can do to keep it.

I've walked past many a classroom and encountered an unsettling horror: a sea of emotionless students with blank stares, their faces pointed in one direction—toward the front of the room, where a lecturer is saging on the stage. And that's not the worst of it. When students are truly checked out, the pervasive glow of laptop screens fills the room—ESPN, Wordle, Biochem homework.

But I got to thinking: why are students—and adults, too—drawn to the stories they consume on their screens? And how can we infuse those same storytelling strategies into our classroom lectures?

If there’s one thing in common about riveting news, entertainment, and social media, it’s that they all have a hook, something that in the first 5 seconds makes the viewer stop in their tracks and pay close attention.

Most trigger fight or flight responses: headlines that strike fear or anger into viewers (hence the term ‘rage baiting’). Others use ethical, proven storytelling strategies to draw the viewer in. In this post, I focus on how we can adapt these strategies and integrate the following into lectures:

Problem-centered stories

Human Likert scale questions

Crafting compelling scenarios

Call and response

Memes, tweets, and reels

A Crucial Disclaimer

In order to successfully use these practices strategies, you have to want to make your class enjoyable for students. If you’re wedded to traditional notions of academic rigor, and respond with the following statements…

I don’t have time to make my lectures more ‘interesting’

Learning is hard; I shouldn’t have to cater to them to get them to pay attention

When I was in school, I learned it just fine this way, so what’s the issue?

No one’s going to spoon feed students in the ‘real world’

…then this article isn’t for you.

I rebut these claims in a recent article about AI and cheating, another topic in which faculty feel they’re competing with technology:

However, if you’re ready to make your lectures more compelling, here are some recommendations from an adjunct professor and professional speaker who tells stories for a living.

Writing a Lecture

What are lectures actually for?

Students need content in order to apply skills in the personal, academic, and professional settings that relate to our disciplines. But consuming content is not learning. Therefore, our lectures should strike a balance between efficiency and effectiveness. When sitting down to plan out your lecture, you should ask yourself: What’s the least amount of content that students need in order to practice this module’s core skills? How can I deliver this content as efficiently and effectively as possible?

The conflict between efficiency and effectiveness, as with many creative endeavors, shows up when deciding what to include in a lecture. For example, you might think that sharing a personal anecdote is a waste of precious class time, when it’s actually the thing that will pull students into your lecture and keep them hooked throughout. On the flipside, you might think you need that fourth case law example to clarify the concept, but all you need is one, maybe two.

See stories and student interaction as necessary incentives to keep students’ attention. If you’re ever stuck deciding whether to include a third example or an interactive element choose the active element every time. Lectures are only as good as the learning-centered activities that follow, so no matter which strategies you use, make sure they’re connected to skills-based, collaborative activities.

5 Ways to Add a Hook to Your Lectures

Problem-Centered Stories

Think about what problems students will go on to solve with the skills they’re learning in your class. Pick a problem that reflects a core value related to your discipline that learners may have strong opinions about.

In my years of doing faculty development, I learned that faculty perceptions of “academic rigor” are varied and hotly contested. Recently, I’ve been starting my keynotes with a detailed story that highlights a teacher-student conflict that illuminates a troubling perception of rigor.

I transition from the story to a central question shown on my PowerPoint slide: “How do I (and my students) discern between learning that is uncomfortable and learning that is unsafe?”

I then offer attendees the content that will help them answer that question. They’re drawn in after realizing that if they don’t answer this question, they could land in the same distressing situation as the instructor in the story.

Here’s a set of questions to answer to help you write an opening story for your lectures:

What is the learning goal or skill that my students will practice in this class session?

Which values, emotions and perceptions will inhibit their ability to practice this skill?

What happens if they don’t adopt this skill? What real or made-up story can I tell that crystalizes the relevance of the skill while playing on those values, emotions and perceptions?

If you’re having trouble coming up with a story, start be generating a few metaphors that encapsulates either a challenge that students will face when applying the skill, or the importance of the skill. Generative AI platforms like Claude or ChatGPT can be a helpful tool in generating metaphors

Human Likert scale questions

Ask Likert scale questions that prompt students to reflect on a topic before you introduce new content. Likert scales are questions you typically see on surveys that read, “on a scale from [insert number] to [insert number], rate [insert measurement].”

If you want to go the extra mile—and have the classroom space to achieve this—you can ask students to create a human Likert scale, where instead of writing their responses on a piece or paper or submitting them virtually, they move to one side of the room or the other based on where they fall on the scale, followed by a brief discussion among students about why they chose their response.

Ideally, this activity should leave students thinking, “The way I’ve understood this topic is too narrow or incomplete, and this lecture will help me think about this problem more expansively.”

Scenarios

Remember that problem-based story you thought about earlier? Instead of telling the full story, create a cliffhanger and let students fill in the blanks for what they think would or should happen. Have them predict the outcome of the story based on what they already know or explain how they would navigate the situation before you reveal how it played out.

If you really want to make a scenario compelling, don’t reveal the answer until the end of the lecture. This builds suspense and gives students something to look forward to at the end of the lecture, increasing their engagement.

Call and Response

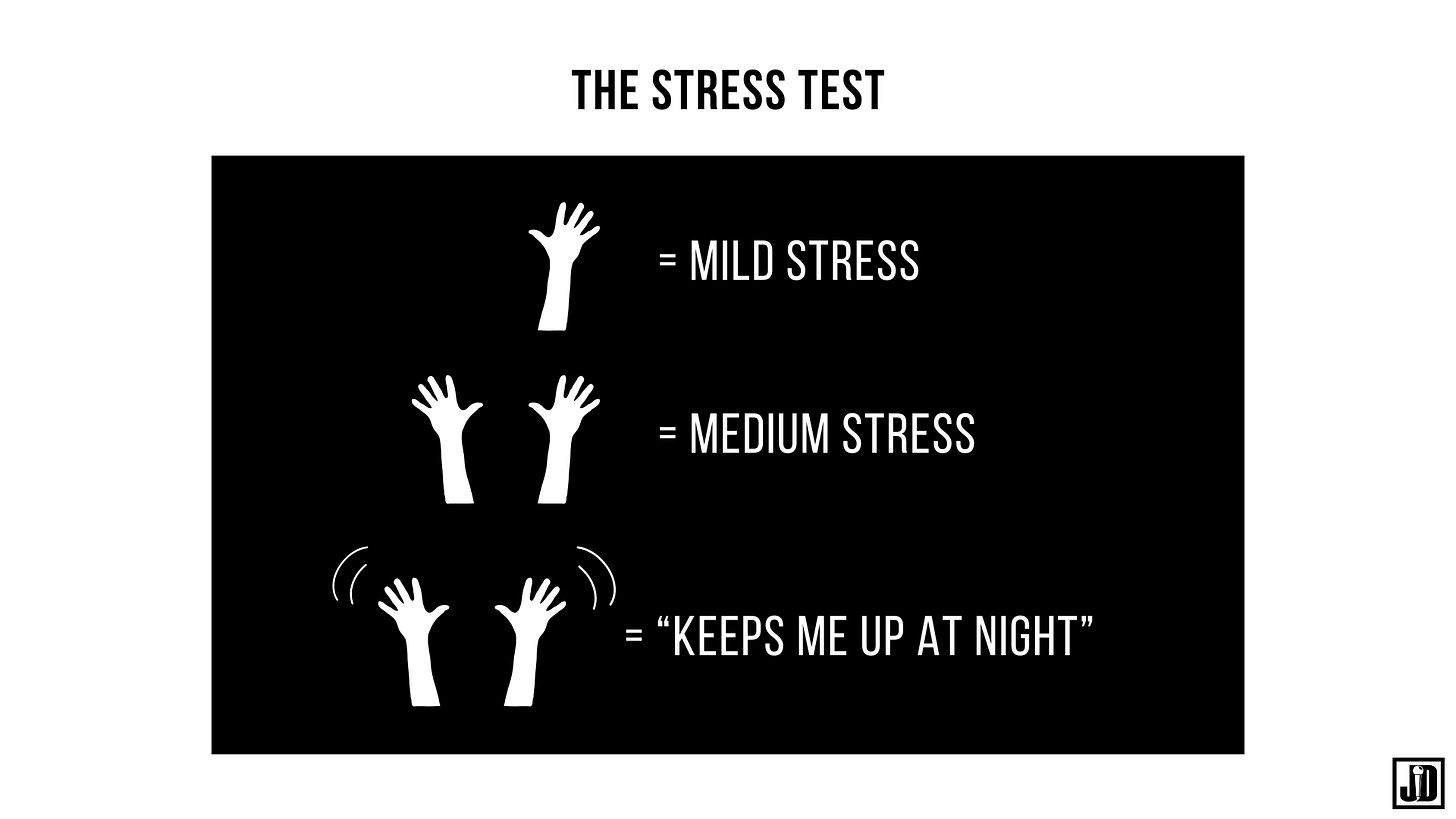

Asking your students to verbally, physically, or visually respond to a series of rapid-fire questions can get their thoughts and energy going. Below is an example of a slide where I ask my high school and college student audiences to rate a series of scenarios as causing mild, medium, or extreme stress for them. Hand motions indicate their ratings: students raise one hand to indicate mild stress, two to indicate medium stress, and frantically wave their hands to indicate extreme stress.

This strategy is simple and adaptable; you could turn it into “‘agree', ‘disagree’ and ‘strongly disagree’”, or a ton of other measurements based on what you want your students to think about and how.

Memes, Tweets, and Reels

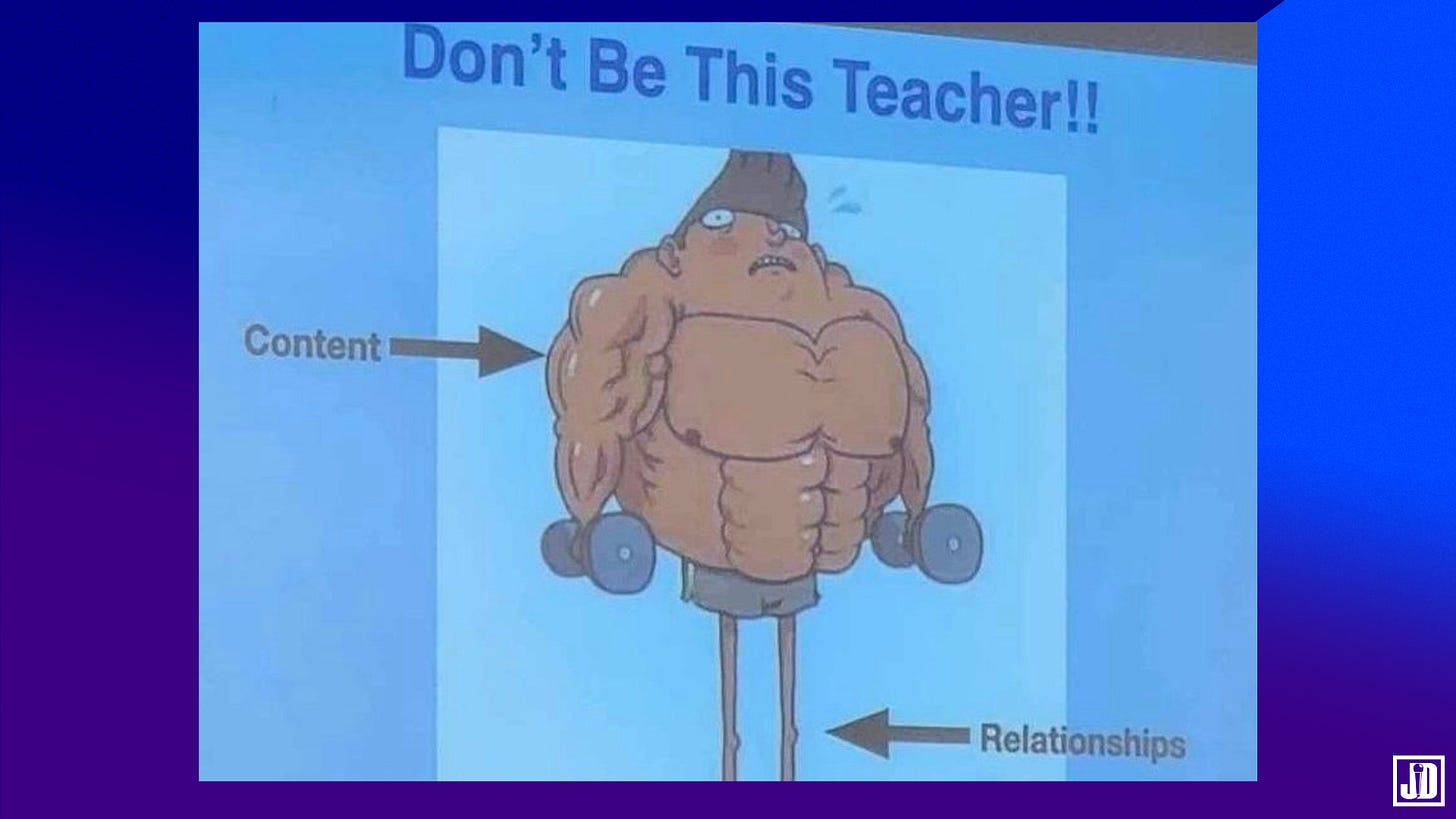

Social media posts are a culturally-relevant, relatable way to add some levity to your lectures. Here’s a meme that I use in my professional development work. It highlights the core challenge I solve through my work in a visually striking, and humorous way:

I found this meme on LinkedIn and added it to one of my slides. Social media is a great place to find memes. If they don’t naturally appear in your feed, try searching #biologymemes on Instagram; substitute biology with your discipline. You’ll find some utterly ridiculous things, but you will likely find one or two diamonds in the rough that you can add to a PowerPoint slide.

Better yet, ask your students to share and create memes, tweets, and short videos that reflect their understanding of the current week’s readings. They can submit them as reflections and discussion posts, and you can include the best ones in your class lecture. The meme or tweet doesn’t have to be spot-on; a loose connection to the topic is enough to get students smiling, thinking, and engaged.

No matter which of these storytelling tactics you decide to try, two things are necessary for their effectiveness: variety and confidence.

Each time your students walk into class, they should know what they’ll be asked to learn and practice, but the how behind it should be a mystery. Don’t beat a tactic to death. Start each class differently. Experiment with where you insert a lecture into your class session. Try different lecture lengths and different opening hooks.

If you’re going to open class with a story, own that story. Move about the classroom, smile at your students, use your whole body to tell the story. Make it spectacular.

I know, this isn’t what you signed up for; speechwriting and acting chops are not in your job description. But if we need students’ attention for them to learn, we must learn how to harness their attention. Your students will thank you for it.

There’s much more to effective lecturing than nailing the opening hook. I’ve got an article in my draft folder titled “Why bad slides are killing your lectures—and how to make them better.”

Look out for that post in the next week or two.

I Need Your Input

What strategies do you use to make your lectures compelling and interactive? Share them with us by leaving a comment below!

You being up rigor and I’m sure that makes most teachers glaze over as they do with other faculty meeting buzz words. However, with the increase of student cheating and the use of electronics, how do you fight that? How do you fight boredom from a core class to an elective? And what about those practices of simply taking away electronics to force the attention?